Between 12th-24th September 2016, Professor Daniel Miller and two researchers on the Why We Post project, Tom McDonald and Xinyuan Wang, will give a series of talks about the findings of the project at nine top universities in HongKong, Guangzhou, Beijing, and Shanghai. This China tour also include the launch (13th September) of the two newly released open-access books: Social Media in Industrial China (Wang, 2016) and Social Media in Rural China(McDonald, 2016). If you can’t be with us in Hong Kong, do join our live-streamed launchand put your questions to the authors.

China was the only country in the Why We Post project with two research sites. One of the reasons for this was because China maintains a greater degree of separation and autonomy in their use of popular digital media when compared to the rest of the world, therefore a global comparative study of social media required close scrutiny of particularly Chinese forms of social media such as QQ, WeChat, and Weibo.

The project includes a considerable amount of material on China such as the two newly released open-access books by UCL Press; one of the five weeks of the Anthropology of Social Media e-course; and a series of films set in the Chinese fieldsites. All of our short films (more than 100) about the uses of social media from our nine field sites have Chinese subtitles, and ourwebsite and e-course are both available in Chinese. Bringing an anthropological understanding of Chinese social media in the context of a comparative study back to China is a big commitment the project’s ultimate goal of turning global research into free global education.

Despite there being Chinese universities that teach anthropology, they have tended to see anthropology as a discipline that deals mainly with minority populations. We believe that the more a population becomes modern and urban and indeed digital, the more we need anthropology. This is because most of life now happens in the private sphere. In a little village perhaps it’s easier to see what’s going on from a surface glance. In a modern city where everyone goes to their own private home after work it is much more difficult. So you need research that is not afraid to follow people into the places where they actually live, which may be inside their smartphones, their social media profiles, as well as inside their homes. Otherwise we will not understand the modern world at all. Asking people questions via superficial surveys is not enough. Anthropologists spend many months living with people in order to be sure they understand what is really going on.

We believe that digital technologies including social media may be more formative of life in China than in almost any other country. While China has great and honourable traditions, the development of what we think of as modern China is relatively recent and relatively fast, taking place at the exact same time that new digital technologies are becoming an integral part of people’s lives. So whether we’re talking about the infrastructure of new cities or the spread of inexpensive smartphones, digital technologies are ubiquitous to the new China, and this means it is particularly important to understand their use and their consequences from a deep and engaged anthropological approach.

We hope that this China tour will introduce digital anthropology as a research tool to the Chinese academy. It is also hoped that the debates and talks will help to formulate key questions for future study within Chinese anthropology. We hope that China will play a key role in these future studies commensurate with its importance as a modern population that is embracing every form of new digital technology, and hopefully also embracing anthropology as the best means for observing and understanding their consequences.

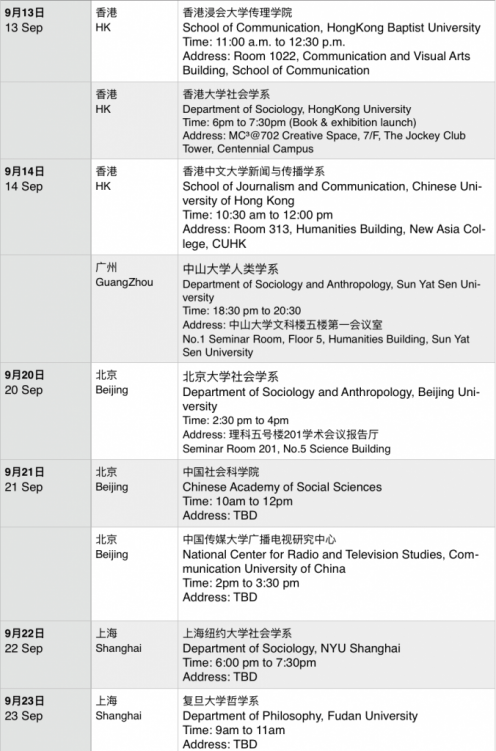

The table below contains details of the talks in this China tour. For further updated information (in Chinese) please see here: http://uclwhywepost.isitestar.vip

About the Author

Xinyuan Wang is a PhD candidate at the Dept. of Anthropology at UCL. She obtained her MSc from the UCL’s Digital Anthropology Programme. She is an artist in Chinese traditional painting and calligraphy. She translated (Horst and Miller Eds.) Digital Anthropology into Chinese and contributed a piece on Digital Anthropology in China.

This post originally appeared on the Global Social Media Impact Study blog. It has been re-posted with permission.