Celebrating World Beard Day

Today is World Beard day! To celebrate, Seb Coxon explains what got him interested in researching how beards are portrayed in medieval German literary texts, and how we make make sense of this. His open access book, Beards and Texts: Images of masculinity in medieval German literature is out now. This post originally appeared on the UCL European Institute blog.

Really, I ought to claim that my interest in this niche topic was sparked by landmark works of medieval European literature. By the Old French Chanson de Roland, for example, with its battles between white-bearded Franks (led by a white-bearded Charlemagne) and their white-bearded heathen adversaries. Or by the medieval Spanish epic, the Poema de Mio Cid, whose long-suffering protagonist takes remarkable pride in his own beard. Or even by the medieval English romance, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where the bushy-bearded Green Knight causes an uproar by deriding the knights at Arthur’s court as ‘beardless boys’.

But the truth is I have a class of students to thank. They were the ones who first drew my attention to a particular episode towards the end of the Nibelungenlied, the foremost medieval German heroic epic. Here, in a twist of Germanic fate, one fearless warrior meets his bloody end at the hands of his friends, whereupon he is mourned by a whole host of suitably devastated heroes, as visualized by the poet: ‘You could see the tears flowing down their beards and chins, for they had suffered a cruel loss.’

So what, if anything, does the almost incidental beard-reference in this scene achieve? My best guess is that it forms part of a strategy of compensation, reasserting the notion of heroic masculinity at a precarious moment. In other words: if warriors are going to cry, then at the very least they should shed tears collectively as a band of bearded brothers and in demonstratively manly fashion.

As a ‘natural’ and naturally conspicuous symbol for masculinity, beards were imbued throughout the Middle Ages with theological, legal and medical significance. In the hands and mouths of poets references to beards, and to beardlessness for that matter, could always serve as a shorthand way of evoking a masculine ideal in any number of complementary or incongruous contexts.

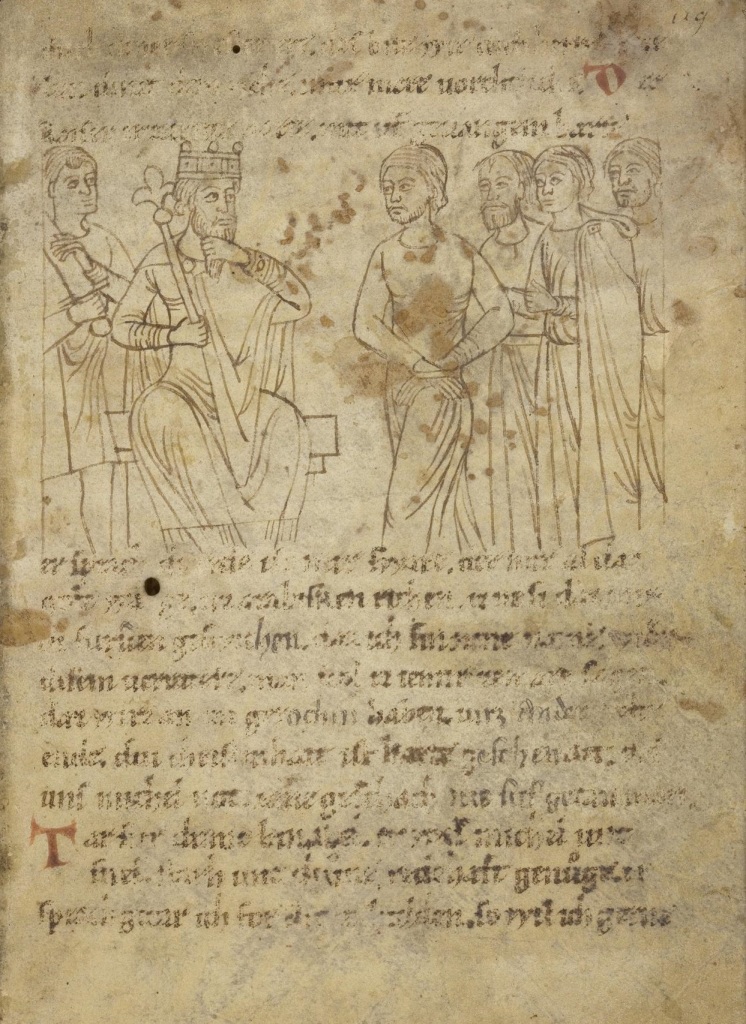

Of course, some figure-types were more likely to be portrayed as bearded than others, although it is always worth looking out for bearded women (not least those virgin saints who miraculously grow a beard to escape unwanted male attention). The bearded king, for example, often wears his majesty in his face, as it were, his beard betokening such credentials for rulership as (sexual) maturity and wisdom. This was in fact a widespread iconographic motif from the twelfth century onwards. And the same motif was exploited by narrative poets too. Thus, a certain Pfaffe Konrad, the author of the German Rolandslied (a reworking of the Chanson de Roland), repeatedly draws attention to Charlemagne’s beard at moments of crisis, when the emperor’s composure is threatened and he expresses his disquiet by grabbing, stroking or shaking his beard at those around him.

Different texts do different things with the same bearded figure-types. In stories where kings are presented as unworthy or fit only for ridicule, their beards are liable to be manhandled, plucked, or even vomited over (as in the widespread fable of the nauseous and somewhat disrespectful philosopher).

Much of this material conforms to one of the cardinal rules of pre-modern storytelling: selective visualization, or rather: choice details pertaining to the appearance of characters tend to be given for a special, thematic reason. Where no such reason existed, the beardedness, or otherwise, of male figures was left to the audience’s (or reader’s) imagination. By contrast, the artists of the miniatures contained in illustrated manuscripts of these same poetic works had no choice but to decide which male figures to beard and which not. The relationship between medieval text and image was very rarely one of straightforward correspondence.

Not infrequently artists had ingenious ideas of their own in matters of the beard. The artist(s) behind some of the pictures designed for Hugo von Trimberg’s very popular moral compendium, Der Renner, for instance, compounds the comic effect of one tale of marital infidelity by emphasizing the affinity between unattractive husband and goat: bearded, outside, and of little interest to the wife indoors, who is embracing her (beardless) young lover. Elsewhere in the same codex, an exquisitely executed beard forms the very focal point of another miniature, framed as it is by the bow and arrow held by the eldest of a dead king’s four sons. Ironically enough, in the macabre trial to discover who among them is worthy of the crown it is the youngest son – the beardless figure to the left of centre – who distinguishes himself by refusing to shoot at his father’s corpse. Sometimes, it would seem, a decorous beard is no more than just that.

About the author

Dr Seb Coxon is Reader in German at the School of European Languages, Culture and Society, UCL.