International Archaeology Day: Snapshots of a growing field

It's International Archaeology Day! To celebrate, Clare Lewis and Gabriel Moshenska bring together critical perspectives on life-writing in the history of archaeology from leading figures in the field. These include studies of archive formation and use, the concept of ‘dig-writing’ as a distinctive genre of archaeological creativity, and reviews of new sources for already well-known lives. Several chapters reflect on the experience of life-writing, review the historiography of the field, and assess the intellectual value and significance of life-writing as a genre. Together, they work to problematise underlying assumptions about this genre, foregrounding methodology, social theory, ethics and other practice-focused frameworks in conscious tension with previous practices.

The chapters collected in Life-writing in the History of Archaeology represent a range of perspectives, approaches and theoretical framings of archaeological life-writing. Together they offer an overview of some of the main strands within the biographical turn in the history of archaeology. In the opening sectiondevoted to critical reflections on the discipline, Kaeser surveys the recent theoretical and methodological developments in the field, based to a considerable extent, as he points out, on the growing body of archive-based research by early career academics. He situates these developments – including the rise of ‘microhistories’ and tensions between studies of individuals and collectives – within their wider contexts in the history and sociology of science. The model of life-writing as microhistorical practice is one that recurs in several of the chapters in this volume. De Armond’s consideration of microhistorical approaches to archaeological life-writing builds on Kaeser’s definitions to consider the marginal, more truly ‘micro’ lives that constitute fragments of the history of archaeology, drawing on the example of the archaeologist Gisela Weyde. De Armond’s

call for a prosopography from the margins considers some potential theoretical and methodological approaches to writing lives that do not fit within more common approaches, and are often erased even in finegrained historical studies: a counterbalance to what she describes as ‘prosopographies of the privileged’.

Several of the chapters in this volume focus on lives in Egyptian archaeology and Egyptology, reflecting in part a resurgence of interest in the history and historiography of these sub-disciplines. Like Abt, Meheuxand others in this volume, Lewis’s study of Egyptologist T. E. Peet’s wartime letters uses a specific and hitherto ignored or neglected set of primary sources, and uses them to shed new light on an otherwise wellknown figure in the discipline. In Lewis’ work these sources are personal letters from Peet, who was serving in the First World War, to his daughter Patricia, then aged just three. Lewis compares these letters to two other

documentary strands in Peet’s archives, noting the complex interplay of public and private lives, agency and self-representation. Gertzen’s chapter grapples with the challenges of writing histories of Egyptology, a field that he argues developed along markedly distinctive lines in German-speaking contexts. In surveying key works in this field to date, Gertzen observes the different forms and influences of history writers’ moral judgements, most notably in studies of scholars active during the Third Reich.

One of the strengths of this volume is its illumination of the variety of angles and perspectives on the history of archaeology that pertain, in often very different ways, to practices of life-writing. Abt’s study of philanthropy and the economic histories of the discipline is one such study, highlighting the particular value of appeals for funding as documents that demonstrate archaeologists’ abilities to write for, and appeal to, non-specialist audiences.

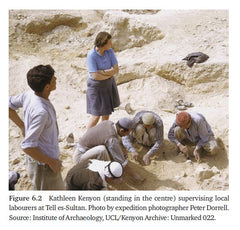

Abt focuses on the relationship between archaeologist James Henry Breasted and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, showing how the need to shape research to the interests of funders could profoundly shape the direction of research project, institutions and individual careers. To the plethora of specific forms of life-writing outlined by Smith and Watson, and discussed earlier, Wagemakers’ chapter adds another: ‘dig writing’ – that is,

histories of specific archaeological excavations told in biographical form and using the same types of sources as life-writing. To illustrate this, he collected a wide range of sources relating to Kenyon’s Jericho excavations including images, letters, film and a dig diary. The account that emerges from these and other sources illustrates the full richness of the ‘dig’ experience:

worries about funding, difficult labour relations, cross-cultural misunderstandings, ill-health, local politics, social relationships and romances, and fallings-out. Wagemakers presents dig writing as a distinct form of history writing, but like life-writing it shares features with related fields, such as microhistory and prosopography Following the more theoretically focused chapters in the first parts of this book, the chapters in the central section illuminate and embody a variety of different sources, aims and approaches to archaeological life-writing. Ansorge’s account of the pleasingly comprehensive Herbert Thompson archive blends description of the holdings – including a physical description of the material itself – with an account of his life and works. In outlining Thompson’s career in Egyptian language studies, Ansorge makes a case for the value of studying an individual scholar primarily through his or her own, singular archive: the wider contexts are present and acknowledged, but viewed from the ‘interior’ of one personal and professional life. The accounts of the movements of archives, personal libraries, ancient texts and artefacts further illustrate the networked nature of life-writing studies, with Cambridge University Library emerging as a notable nexus in the trajectories of so many of these

materials. The uses, limitations and absence or survival of personal letters as a source for life-writing is one of the recurring themes in this volume.

Moshenska’s chapter focuses on the correspondence between two scholars of ancient Egypt in the early nineteenth century: the British surgeon Thomas Pettigrew and the Dutch curator Conrad Leemans. The letters that Leemans sent over several years combine personal warmth and professional minutiae, and also shed light on the operation of intellectual networks:

Leemans asks Pettigrew’s assistance for several of his acquaintances passing through London, including the young archaeologist Karl Lepsius.

As we have discussed elsewhere in this chapter, much of the most valuable recent work in archaeological life-writing has focused on the hitherto marginalised. Stewart’s study of the scholar of Roman Britain Margerie Venables Taylor includes several of the mechanisms by which women’s contributions to the development of archaeology have been neglected, including under-representation in academic posts and overshadowing by prominent men – in this case Francis Haverfield.

In examining the entanglement of Haverfield and Taylor’s work and careers, Stewart highlights the gap left by Taylor’s deliberate disposal of her personal papers. She examines Taylor’s obituary of Haverfield – a significant piece of life-writing – to argue that Taylor’s subsequent labours at the Roman Society and its journal can be understood as the posthumous continuation of her longstanding collaborative work with Haverfield, in part alongside his other protégé R.G. Collingwood.

In examining the entanglement of Haverfield and Taylor’s work and careers, Stewart highlights the gap left by Taylor’s deliberate disposal of her personal papers. She examines Taylor’s obituary of Haverfield – a significant piece of life-writing – to argue that Taylor’s subsequent labours at the Roman Society and its journal can be understood as the posthumous continuation of her longstanding collaborative work with Haverfield, in part alongside his other protégé R.G. Collingwood.

Historical disputes are often intellectually stimulating topics for study, and Freed’s examination of Alfred-Louis Delattre and Paul Gauckler’s work in Tunisian archaeology provides detailed context for the two men as well as for their conflict: a French conflict, as she describes it, on Tunisian soil. This dispute developed over several years and encompassed the most powerful dimensions of French society including church, state and the École Normale. Freed demonstrates the longstanding impacts of this dispute in the contemporary reception of both men’s work, and argues for the importance of histories and life-histories in the practice of archaeology. Past controversies also shape Murray’s study of Hugh Falconer. This chapter and Falconer’s remarkable achievements are a reminder of the startling breadth of interests and achievements that characterised the intellectual lives of Victorian polymaths, ranging across medicine, botany and palaeontology as well as archaeology. It is also a reminder of the deep roots in Empire that enabled and shaped many of these interests. Murray outlines the intellectual disputes that coloured Falconer’s legacy even in the immediate aftermath of his death and shed light on a life’s work that has hitherto appeared in fragments, mostly as it relates to other, more prominent scholars of his era.

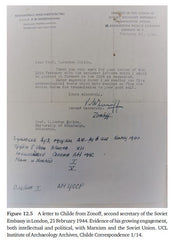

In his critical engagements with the methods of life-writing, Kaeser highlights the challenges of the archive, such as the illusory ‘reality effect’ of primary sources, and discusses the difficulties that biographers can face in engaging with earlier, less critical studies of their subjects. Few archaeologists have been so extensively studied since their death as Vere Gordon Childe, but Meheux’s chapter provides a novel perspective, drawing on the files accumulated by the UK Security Service over decades of surveillance and monitoring.

Meheux offers a subtle reinterpretation of Childe’s relationship with communism and with left-wing culture more broadly. While taking an appropriately cautious approach to the files, she offers a subtle interpretation of Childe’s ideologies and activism, often focused around pacifism, in the nuanced and changing contexts of left wing political activism from the First World War to the Cold War.

The final section of this book focuses on more personal reflections on the practice of archaeological life-writing. Moro Abadía’s chapter is built around fragments of diary that he wrote during a study trip in Paris, while researching archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan. He describes his engagement with literature and documents, as well as meetings with colleagues, as he traces inter alia the influences of Anette Laming- Emperaire’s work on Leroi-Gourhan’s thought. The diary and its analysis is an exercise in reflexivity, as well as an intriguing insight into the working practices of a historian of archaeology. Gill’s chapter reflects on his own prolific writings on lives in Classical archaeology, emerging from provenance and collections history research in a museum context, and later in writing on the development of the discipline. He describes his contributions to a range of life-writing project including several studies of Winifred Lamb, ranging over several years and the discovery of new sets of sources, as well as work on the revision and expansion of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

At the close of the book, Challis’ study of artist Ann Mary Severn Newton describes a brief, brilliant life caught between the demands of family, finances and professional practice in archaeological illustration. She reflects on the affective dimensions of life-writing, including her own struggles in conducting this research, and the value of greater critical consideration of the connections between biographers and their subjects.

Challis’ moving description of the connections and echoes between her own life and Newton’s offer insights into why and how scholars approach life-writing in practice, and might also need to step away again. Much life-writing is based on a sense of connection or kinship, and as Challis shows it can spark empathy but also grief and sadness. It remains for lifewriting practices to better engage with these affective aspects, not least for their critical significance, and for the valuable perspectives that they shed on past lives.

New directions

Where next for archaeological life-writing? Many of the current trends are positive ones, including the search for forgotten or marginalised lives in archaeology and criticism of the focus on fieldwork and fieldworkers at the expense of other spheres of research and discovery. In our research we recently encountered files of printed emails from the 1990s, some reused as notepaper: an already-anachronistic material practice that points to the increasing value and necessity of natively digital sources and archives, alongside the widespread and commendable digitisation of archives and collections. As digital media are themselves becoming the subject of archaeological excavations, the shape of much future work comes into focus.

An interesting recent trend in life-writing has been the rise of graphic novel biographies. Some of the best-known of these focus on the lives of ordinary people, such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Alison Bechtel’s Fun Home. Others have focused on important figures, such as the multi-volume March on the life of US politician and activist John Lewis, who co-authored the trilogy. A growing number of these books are focused on the lives of scholars and scientists, and in most cases intertwine narratives of their intellectual and personal histories. An outstanding example of this is Logicomix, an exploration of Bertrand Russell’s research into the philosophy of mathematics, an otherwise bone-dry topic brought to life through beautiful artwork and a layered narrative. Naomi Miller’s Drawing on the Past is a beautiful example of life-writing through artworks and text that draws on the distinctive visual cultures of archaeological fieldwork.

From an academic perspective, the most significant recent research project in our field was the Collective Biography of Archaeology in the Pacific project based at Australian National University from 2015 to 2020. This was a wide-ranging initiative intended to establish a field of scholarship around the history of Pacific archaeology, and with specific aims to highlight the forgotten and erased histories of women archaeologists and indigenous scholars and collaborators. The project took an explicitly international perspective, ranging across the Pacific and studying the work of German, French and Russian archaeologists, amongst others. The outputs of this project represent a significant advance in the field of Pacific archaeology and in the historiography of archaeology more generally, and it would be good to see projects of similar scale and ambition, with explicitly biographical scope, elsewhere in the world.

One of the pleasures of bringing together this book has been a greater appreciation for the vast number of fascinating lives in archaeology, across the centuries and around the world. Their stories shed light on times and places, intellectual currents and world events. Some of the most striking and rewarding parts of reading these studies comes from spotting points of connection between individuals. Overlaps in place and time, mutual friends or contacts, illicit relations, forgotten collaborations and small favours: the threads that connect individuals into social, economic and scholarly networks, which in turn set out the frameworks for disciplinary histories.

An excerpt from Life-writing in the History of Archaeology: Critical perspectives, edited by Clare Lewis and Gabriel Moshenska.

Clare Lewis is a lecturer (teaching) in Arts and Sciences at UCL.